Maurice Herzog’s Annapurna (1951) is a firsthand account of one of the most harrowing and triumphant feats in mountaineering history.

In 1950, Herzog led a Franco-Alpine expedition to summit Annapurna, a Himalayan peak that no human had ever set foot on. In fact, no human had stood atop any of the fourteen "eight-thousanders" – mountain giants stretching above 8,000 meters.

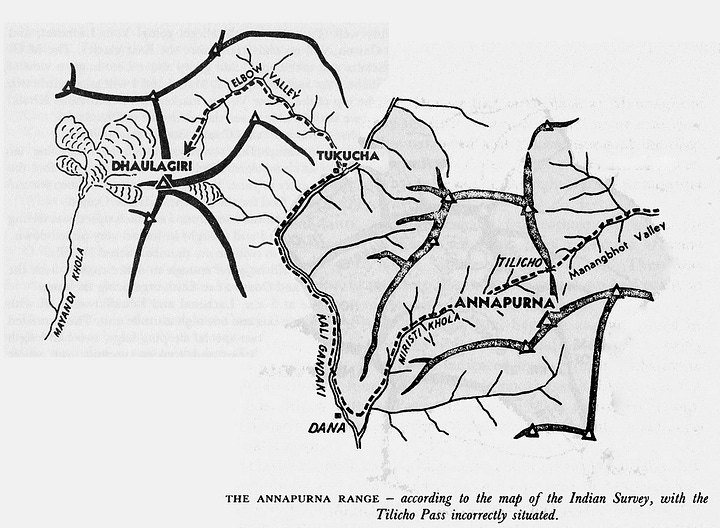

And Herzog's team did it without oxygen, reliable weather reports, detailed maps, or the specialised gear we take for granted today.

"Victory over a mountain is meaningless—it is a victory over ourselves that counts."

A brutal ascent, an even more brutal descent, and a test of human endurance, this was an expedition that left Herzog and his team permanently altered—physically, mentally, and historically.

Annapurna is raw, immediate, and relentless. If you want to feel the cold, the hunger, the exhaustion, and the sheer willpower it takes to survive when survival isn’t guaranteed, this book will drag you up the mountain with Herzog and leave you breathless at the top.

A Thin Line Between Triumph and Tragedy

The first half of the book is an expedition journal, full of logistical details, scouting missions, and the kind of camaraderie that only forms when men are marching toward potential death together. There’s a mix of optimism and calculation, an almost naive determination to succeed.

Herzog writes with a kind of preordained certainty—as if failure isn’t an option, even though failure would be the more reasonable outcome.

When he finally reaches the summit, he delivers one of the most famous lines in mountaineering literature:

"We had conquered Annapurna. It was a victory for all mankind."

It’s grand, it’s theatrical, and it’s absolutely Herzog. The problem? The descent nearly kills them all.

Herzog and his team suffer frostbite so severe that fingers, toes, and entire sections of their feet turn black and dead. They lose equipment, fall into crevasses, and nearly die multiple times. Herzog himself is barely conscious for much of it, hallucinating through a haze of pain and exhaustion.

The most horrifying part isn’t just the injuries—it’s the sheer helplessness. A summit is a moment of triumph, but no one tells you how to get down when your body is broken and every step is agony. By the time they reach safety, the cost of their success is brutally clear. Herzog loses all his toes and most of his fingers. Others suffer similarly. The mountain doesn’t let them go unscathed.

Where Herzog shines

Herzog's prose, even in translation, achieves moments of transcendent beauty.

“I felt as though I were plunging into something new and quite abnormal. I had the strangest and most vivid impressions, such as I had never before known in the mountains. There was something unnatural in the way I saw Lachenal and everything around us. I smiled to myself at the paltriness of our efforts, for I could stand apart and watch myself making these efforts. But all sense of exertion was gone, as though there were no longer any gravity. This diaphanous landscape, this quintessence of purity—these were not the mountains I knew: they were the mountains of my dreams.”

The book's finest passages occur not at the moment of triumph but in the aftermath of disaster, when Herzog confronts his own mortality and permanent disability.

"In the droplets that fell from my fingers I could see a symbol of life ebbing away."

These reflections elevate Annapurna from adventure yarn to philosophical meditation.

“The silence awed me. I no longer suffered. My friends attended to me in silence. The job was finished, and my conscience was clear. Gathering together the last shreds of energy, in one last long prayer, I implored death to come and deliver me. I had lost the will to live, and I was giving up—the ultimate humiliation for a man, who, up till then, had always taken a pride in himself. This was no time for questions nor for regrets. I looked death straight in the face, besought it with all my strength. Then abruptly I had a vision of the life of men. Those who are leaving it for ever are never alone. Resting against the mountain, which was watching over me, I discovered horizons I had never seen. There at my feet, on those vast plains, millions of beings were following a destiny they had not chosen. There is a supernatural power in those close to death. Strange intuitions identify one with the whole world. The mountain spoke with the wind as it whistled over the ridges or ruffled the foliage. All would end well. I should remain there, forever, beneath a few stones and a cross. They had given me my ice-axe. The breeze was gentle and sweetly scented. My friends departed, knowing that I was now safe. I watched them go their way with slow, sad steps. The procession withdrew along the narrow path. They would regain the plains and the wide horizons. For me, silence.”

What might disappoint you

Time has revealed significant gaps between Herzog's account and those of his teammates. Notably, Lachenal's posthumously published diary contradicts key elements of Herzog's heroic narrative.

"We were at the end of our tether... the summit meant little to me," Lachenal wrote, a stark contrast to Herzog's portrayal of unified purpose.

These discrepancies don't necessarily diminish the book—they transform a simple adventure story into a complex study of memory, ego, and historical record.

Herzog is unwavering in his belief that the expedition was a victory, despite the suffering. But was it? Was summiting Annapurna worth the amputations, the near-deaths, the lifelong disabilities?

Herzog tells you it was—and expects you to believe him. He stands no dissent within his team or within his readers. You'll notice the near-deification of Herzog in the text—a self-aggrandisement that later climbers and historians have vigorously disputed.

There's also the lingering stench of colonial patronising permeating the text, a reflection of its era but jarringly tone-deaf today.

“But like everything else in India, the problem would be solved, provided there was no hurry.”

The expedition's relationship with local communities and hired porters reveals much about post-war European attitudes toward non-Western cultures.

"They worked like beasts of burden," Herzog writes in what he believes is admiration, revealing volumes about the expedition's power dynamics.

The Verdict: Brutal, Exhilarating, Flawed, Essential

Annapurna is gripping, visceral, and written with the urgency of a man who has lived through something unimaginable. But it’s also a product of its time—romanticising exploration, glorifying suffering, and refusing to dwell on doubt. Herzog controlled the expedition's narrative with iron determination, allegedly seizing team members' journals and photographs.

Regardless, Annapurna has sold over 11 million copies, becoming the best-selling mountaineering book ever published. It established the template for modern adventure literature: the page-turning narrative, philosophical asides, and unflinching documentation of physical suffering.

Read Next:

For more mountaineering drama, try Jon Krakauer's Into Thin Air and Joe Simpson's Touching the Void. Both inherit Herzog's unflinching approach to disaster while offering more nuanced perspectives on risk, ambition, and mortality.

If you’re looking for something that captures the spiritual pull of the mountains, Peter Matthiessen’s The Snow Leopard is more meditative.

For broader explorations of human endurance, try Alfred Lansing's Endurance about Shackleton's Antarctic survival against impossible odds.

And if you want a novel that explores survival against impossible odds, try The Road by Cormac McCarthy—because Herzog’s descent feels just as harrowing as an apocalyptic wasteland.