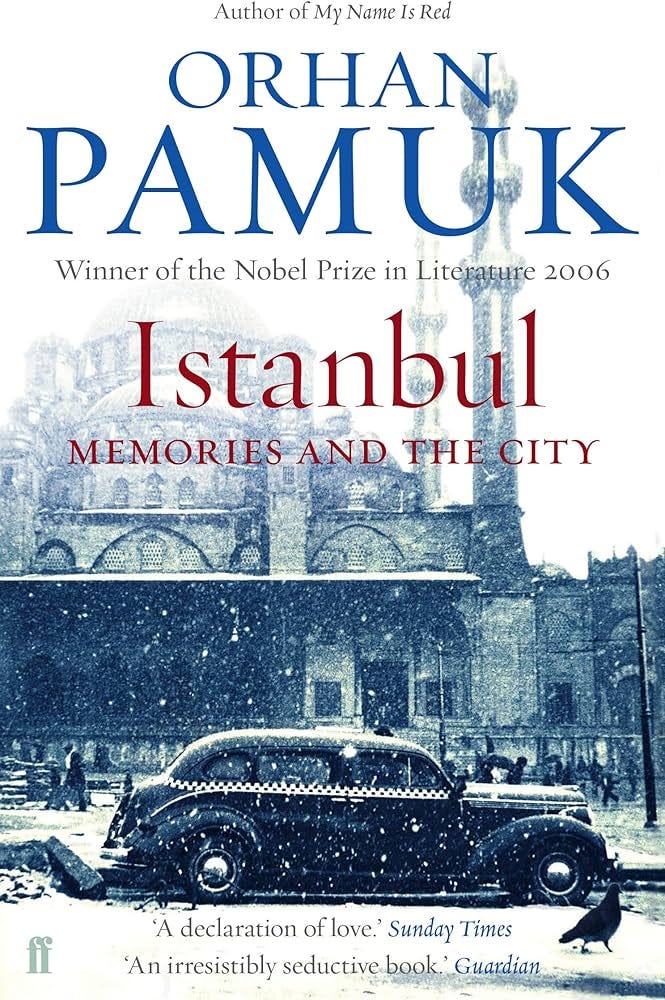

Orhan Pamuk’s Istanbul: Memories and the City (2003) is not your standard memoir. It is neither a chronological account of a writer’s life nor a straightforward love letter to a city.

Instead, it is something more elusive, more introspective—a deeply personal meditation on memory, melancholy, and the strange, bittersweet weight of growing up in a place that feels like it is always losing something.

“In Turkish we have a special tense that allows us to distinguish hearsay from what we’ve seen with our own eyes; when we are relating dreams, fairy tales, or past events we could not have witnessed, we use this tense.”

A Boy and His City

Pamuk grew up in a decaying Ottoman mansion in Istanbul, a city caught between its imperial past and its uncertain modernity.

His childhood is one of fading aristocracy—family feuds, crumbling apartments, and the suffocating expectation that he will become an architect instead of the writer he longs to be.

“The first thing I learned at school was that some people are idiots; the second thing I learned was that some are even worse.”

The Istanbul of his youth is not the glittering crossroads of civilizations so often romanticised in travelogues.

“Like most Istanbul Turks I had little interest in Byzantium as a child. I associated the word with spooky, bearded, black-robed Greek Orthodox priests, with the aqueducts that still ran through the city, with the Hagia Sophia and the red brick walls of old churches. To me, these were remnants of an age so distant there was little need to know about it. Even the Ottomans who conquered Byzantium seemed very far away.”

Instead, it is a city of fog, of half-ruined palaces, of old men staring at the Bosphorus as if trying to remember something they have lost.

“When there is not a breath of wind, the waters sometimes shudder as if from inside and take on the finish of washed silk.”

This is not just Pamuk’s story; it is the city’s story. He weaves his personal history into Istanbul’s own, blending family drama with the ghosts of Ottoman splendour.

“When İstanbullus grow a bit older and feel their fates intertwining with that of the city, they come to welcome the cloak of melancholy that brings their lives a contentment, an emotional depth, that almost looks like happiness. Until then they rage against their fate.”

Pamuk’s Istanbul is not just a place—it is a mood. And that mood is hüzün, a Turkish word that he describes as a kind of communal melancholy, a nostalgia not for what was, but for what could have been.

"Hüzün does not just paralyze the inhabitants of Istanbul; it also gives them poetic license to be paralyzed."

Where Pamuk shines

Pamuk's genius lies in his ability to make you see Istanbul through multiple lenses simultaneously - the wide-eyed wonder of his childhood self, the analytical gaze of his adult persona, and the perspectives of numerous Western travellers and Turkish writers who've attempted to capture the city's essence.

“Melling’s is an insider’s eye. But because the İstanbullus of his time did not know how to paint themselves or their city—indeed, had no interest in doing so—the techniques he brought with him from the West still give these candid paintings a foreign air. Because he saw the city like an İstanbullu but painted it like a clear-eyed Westerner, Melling’s Istanbul is not only a place graced by hills, mosques, and landmarks we can recognize, it is a place of sublime beauty.”

And:

“Writers like Pierre Loti, by contrast, make no secret of loving Istanbul and the Turkish people for the opposite reason: for the preservation of their eastern particularity and their resistance to becoming western.”

The integration of black-and-white photographs by Ara Güler and others isn't mere decoration - it's fundamental to the book's exploration of how Istanbul's soul has been captured and interpreted.

“To see the city in black and white is to see it through the tarnish of history: the patina of what is old and faded and no longer matters to the rest of the world. Even the greatest Ottoman architecture has a humble simplicity that suggests an end-of-empire gloom, a pained submission to the diminishing European gaze and to an ancient poverty that must be endured like an incurable disease. It is resignation that nourishes Istanbul’s inward-looking soul.”

These images, often showing the city in various states of decay, perfectly complement Pamuk's meditation on decline and transformation.

“Still, the melancholy of this dying culture was all around us. Great as the desire to westernize and modernize may have been, the more desperate wish was probably to be rid of all the bitter memories of the fallen empire, rather as a spurned lover throws away his lost beloved's clothes, possessions, and photographs. But as nothing, western or local, came to fill the void, the great drive to westernize amounted mostly to the erasure of the past; the effect on culture was reductive and stunting, leading families like mine, otherwise glad of republican progress, to furnish their houses like museums.”

Pamuk draws inspiration from flâneurs like Baudelaire and Turkish writers like Yahya Kemal and Tanpınar, excavating layers of cultural memory.

“But it is these four heroes, whom I will discuss from time to time in this book, whose poems, novels, stories, articles, memoirs, and encyclopedias opened my eyes to the soul of the city in which I live. For these four melancholic writers drew their strength from the tensions between the past and the present, or between what Westerners like to call East and West; they are the ones who taught me how to reconcile my love for modern art and western literature with the culture of the city in which I live.”

His references to these writers aren't mere name-dropping - they form a crucial dialogue about how cities are imagined and remembered.

What might disappoint you

Pamuk’s introspection is both his greatest strength and his biggest weakness. If you are expecting a vibrant, colourful travelogue filled with bustling markets and spicy street food, you will not find it here.

This is not Istanbul as a postcard—it is Istanbul as a faded photograph, curling at the edges.

“Is this the secret of Istanbul—that beneath its grand history, its living poverty, its outward-looking monuments, and its sublime landscapes, its poor hide the city’s soul inside a fragile web?”

His obsession with hüzün can feel repetitive at times, as if he is circling the same thought without quite moving forward.

“Likewise, the hüzün in Turkish poetry after the foundation of the Republic, as it, too, expresses the same grief that no one can or would wish to escape, an ache that finally saves our souls and also gives them depth. For the poet, hüzün is the smoky window between him and the world. The screen he projects over life is painful because life itself is painful. So it is, too, for the residents of Istanbul as they resign themselves to poverty and depression. Imbued still with the honour accorded it in Sufi literature, hüzün gives their resignation an air of dignity, but it also explains why it is their choice to embrace failure, indecision, defeat and poverty so philosophically and with such pride, suggesting that hüzün is not the outcome of life’s worries and great losses, but their principal cause.

And while his reflections on art and literature add depth, there are moments when the book feels more like an academic essay than a memoir.

The Verdict: A Love Letter to Loss

Istanbul is a book for those who understand that love and sadness are often the same thing.

It is for readers who appreciate nostalgia, who savour slow, poetic prose, who do not mind lingering in a city’s shadows rather than rushing through its grand avenues.

“If we’ve lived in a city long enough to have given our truest and deepest feelings to its prospects, there comes a time when—just as a song recalls a lost love—particular streets, images, and vistas will do the same.”

Winner of numerous awards, including the Prix Méditerranée Étranger, the book has become a touchstone for writing about how cities shape our identities and how memory shapes our understanding of place.

Read Next:

If you are drawn to literary memoirs steeped in place and memory, Ernest Hemingway's A Moveable Feast captures a different kind of nostalgia—Paris instead of Istanbul, but the same longing for a lost world.

For fiction, dive into Elif Shafak's The Bastard of Istanbul, or Teju Cole’s Open City, which captures the hüzün of New York caught between the past and the present.

And, if you want more Pamuk, The Museum of Innocence takes his obsession with memory and loss and turns it into a devastating love story.