Roman Emperor Speaks from Beyond the Grave

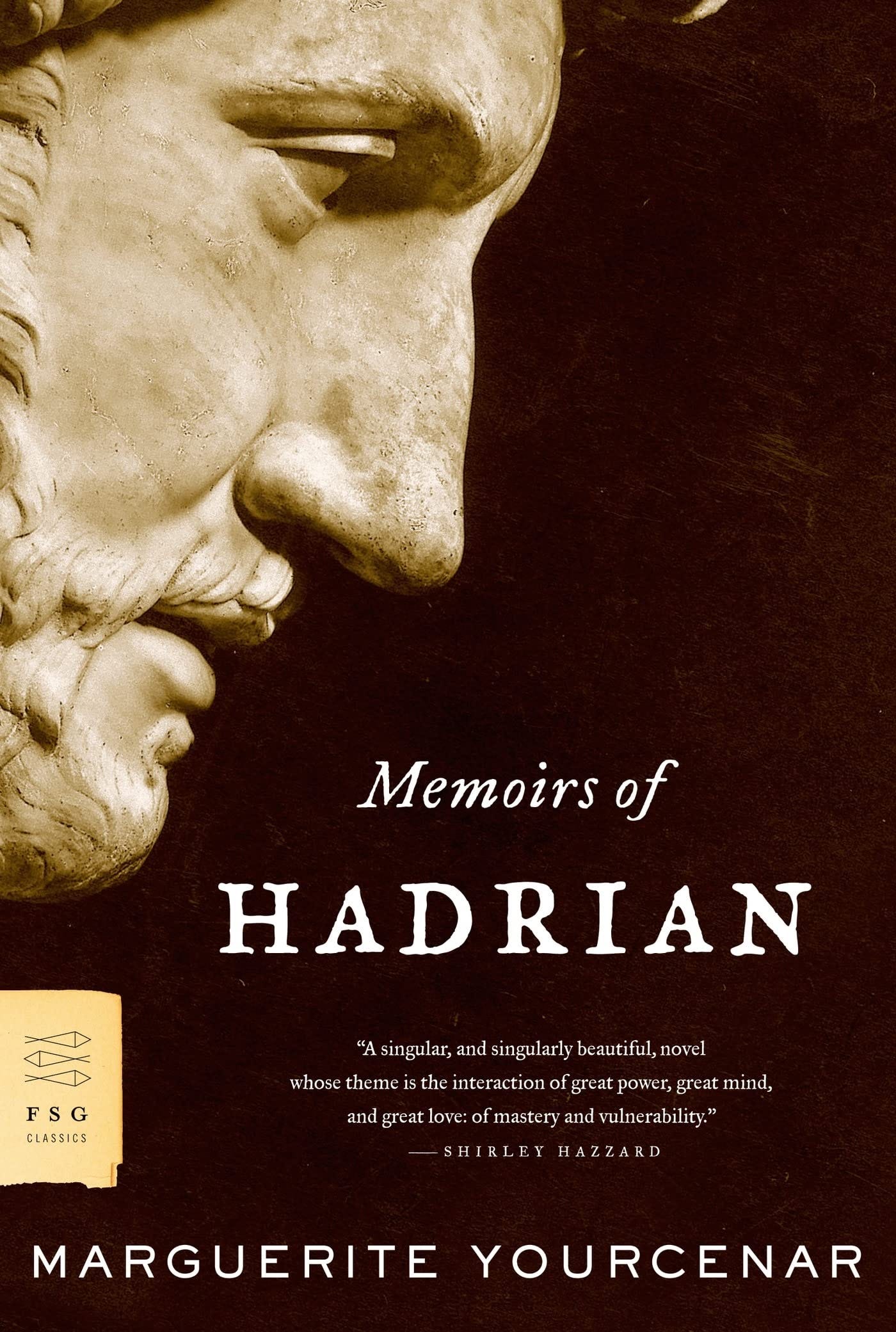

Review of Marguerite Yourcenar's "Memoirs of Hadrian" (1951)

If I, Claudius is a scandalous gossip column on Rome’s worst rulers, Marguerite Yourcenar's Memoirs of Hadrian (1951) is its philosophical, poetic counterpoint—a meditation on power, love, and mortality written by an emperor who has already lost everything.

Marguerite Yourcenar doesn’t just write about Hadrian; she becomes him.

The novel reads like a personal letter from the dying ruler to his adoptive grandson, Marcus Aurelius, reflecting on his life with a mixture of pride, regret, and unflinching honesty.

This isn’t a book you read so much as sink into, and it demands patience. If you’re looking for betrayals, stabbings, and orgies, you’re in the wrong place.

But if you want to sit at the feet of a dying philosopher-king as he wrestles with what it meant to hold the world in his hands, you won’t find a better guide.

Feels like found documentation

Drawing from ancient sources including Hadrian's own fragmentary writings, the Historia Augusta, and countless archaeological records, Yourcenar creates a historical novel that reads like found documentation.

"A single line from historians allows us to reconstruct a life," she writes in her notes, and she proves it with every page.

Her Hadrian, unlike the madmen before him, isn’t a tyrant or a sadist. He’s a builder, a thinker, a traveler, a lover of beauty, and—most importantly—a man who knows that power is fleeting.

"I felt responsible for the beauty of the world."

Rome is at its peak under his reign, but he’s wise enough to know that empires are just sandcastles waiting for the tide.

“The founding of libraries was like constructing more public granaries, amassing reserves against a spiritual winter which by certain signs, in spite of myself, I see ahead…”

He reflects on his military campaigns, his reforms, his travels across the empire, and his love for Greek culture.

“The landscape of my days appears to be composed, like mountainous regions, of varied materials heaped up pell-mell. There I see my nature, itself composite, made up of equal parts of instinct and training. Here and there protrude the granite peaks of the inevitable, but all about is rubble from the landslips of chance.”

But the heart of the novel is his relationship with Antinous, the young Greek lover whose death haunts him.

“Of all our games, love's play is the only one which threatens to unsettle the soul.”

Hadrian, who has conquered nations, is utterly powerless in the face of loss. He deifies Antinous, builds cities and temples in his name, but it’s never enough.

“But even the longest dedication is too short and too commonplace to honor a friendship so uncommon.”

His grief runs through the novel like an underground river, always present, shaping everything.

“I was willing to yield to nostalgia, that melancholy residue of desire.”

What Yourcenar gets right:

Yourcenar seamlessly weaves documented historical facts with psychological insight.

Her Hadrian is entirely plausible: a philosopher-emperor who built walls while dreaming of breaking down barriers between cultures.

"I was beginning to find that the word 'barbarian' had no meaning."

Hadrian isn’t perfect—he can be ruthless, arrogant, and self-justifying—but he’s self-aware enough to recognise it.

“The true birthplace is that wherein for the first time one looks intelligently upon oneself.”

You'll be captivated by the intimacy of Hadrian's voice and the beauty of Yourcenar's prose (even in Grace Frick’s brilliant English translation).

Yourcenar spent decades crafting this book, and every sentence feels polished to perfection. The prose is lyrical without being overdone, intimate without feeling indulgent.

Her Hadrian contemplates life, duty, love, and the weight of ruling an empire, but it never feels like a lecture.

"I have come to think that great men are characterized by the violent contrast between the problems they solve with ease and those that paralyze them completely."

And elsewhere:

“Our great mistake is to try to exact from each person virtues which he does not possess, and to neglect the cultivation of those which he has.”

His reflections are deeply personal, filled with wisdom but also self-reproach. Towards the end, he writes:

“Little soul, you have wandered and strayed, now you have no choice but to go.”

It’s a farewell to himself, to his own life, and to the world he once ruled.

"Meditation upon death does not teach one how to die; it does not make the departure more easy, but ease is not what I seek."

What might disappoint you

If you don’t like introspective, slow-moving novels, Memoirs of Hadrian will test your patience.

There’s no plot in the traditional sense—no twists, no betrayals, no climax.

It’s just a long, beautifully written monologue.

That’s either mesmerising or exhausting, depending on what you want from historical fiction.

And while Hadrian’s love for Antinous is central to the book, Antinous himself remains elusive.

We see him only through Hadrian’s eyes, as an idealised figure rather than a fully fleshed-out person.

That distance is intentional—this is Hadrian’s memory, after all—but it can feel frustrating.

The Verdict: Definitely worth the hype

Absolutely—if you’re in the right mood. This isn't light reading - it's a meditation on power, death, and the meaning of civilisation itself.

The book is both timeless and timely, as relevant to understanding power and responsibility today as it was when first published.

“Laws change more slowly than custom, and though dangerous when they fall behind the times are more dangerous still when the presume to anticipate custom.”

Hadrian may have built walls to keep out invaders, but in this novel, he lets you inside his mind completely. It’s a rare gift.

“I knew that good like bad becomes a routine, that the temporary tends to endure, that what is external permeates to the inside, and that the mask, given time, comes to be the face itself.”

Read Next:

“The written word has taught me to listen to the human voice, much as the great unchanging statues have taught me to appreciate bodily motions. On the other hand, but more slowly, life has thrown light for me on the meaning of books.”

For another novel that turns a historical figure into a deeply human voice, try John Williams's Augustus. It has a more structured plot but captures a similar reflective tone.

If you want non-fiction, Mary Beard’s SPQR and Emperor of Rome give a sharp, modern take on the Rome Hadrian knew.

And if you want pure philosophical musings from an emperor himself, go straight to Marcus Aurelius's Meditations—the man to whom Hadrian’s letter is addressed.