Rome wasn’t built in a day, but it sure burned fast.

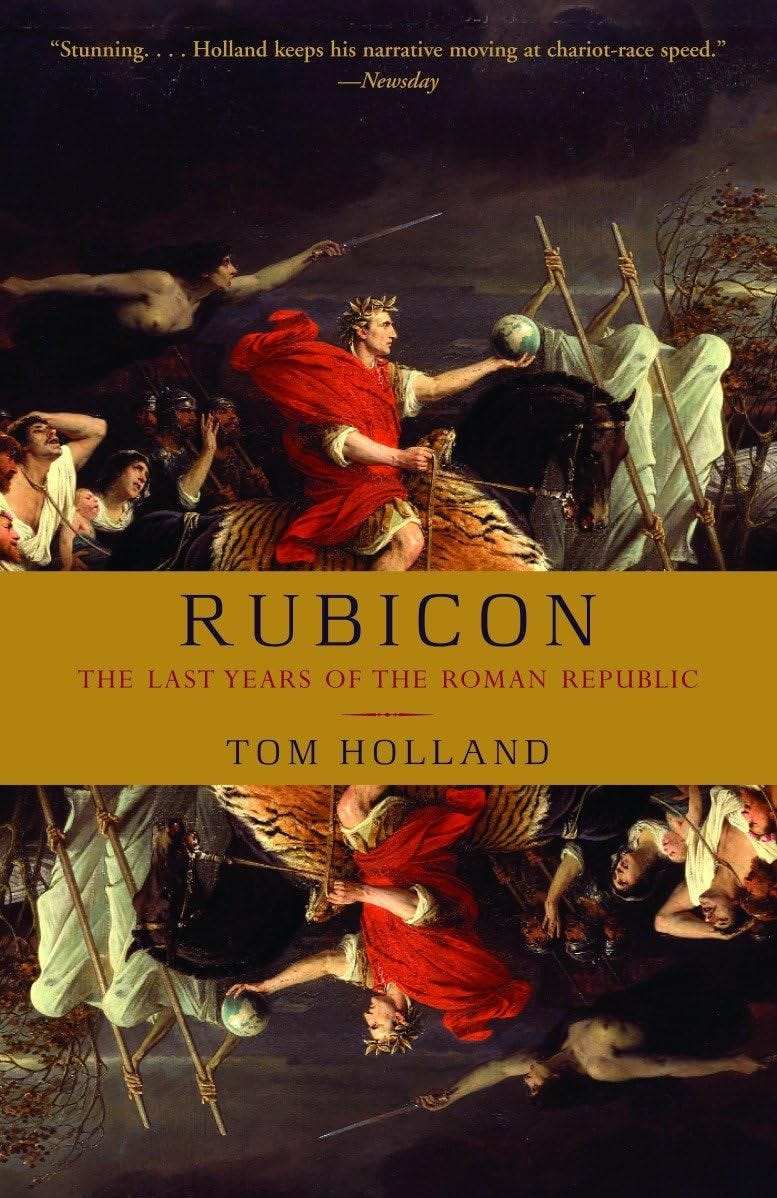

Tom Holland’s Rubicon: The Last Years of the Roman Republic (2003) is a front-row seat to one of history’s greatest implosions—the messy, violent, and utterly gripping fall of the Roman Republic.

"Nothing quite like it had ever happened before."

You know how this story ends. Julius Caesar crosses the Rubicon, the Republic crumbles, and the Roman Empire is born.

But Holland makes sure you feel every twist of the knife along the way.

This isn’t dry history—it’s a high-stakes political thriller where every senator has a dagger behind his back, and every decision inches Rome closer to disaster.

The Republic was always a powder keg

If you think Rome was a noble experiment in democracy that tragically fell apart, Holland has news for you: the Republic was never built to last.

It was an unstable, cut-throat system where power belonged to an elite few, elections were corrupt, and populist leaders were either assassinated or exiled.

Describing the political class that claimed to represent the people while systematically exploiting them, he notes:

"The senators were oligarchs who posed as democrats."

And for all their supposedly democratic sentiment, Romans never missed a dynastic beat at the heart of their choices:

“The Roman character had a strong streak of snobbery: effectively, citizens preferred to vote for families with strong brand recognition, electing son after father after grandfather to the great magistracies of state, indulging the nobility’s dynastic pretensions with a numbing regularity.”

It was a miracle the Republic lasted as long as it did.

Drawing from Plutarch, Suetonius, and Cicero among others, Holland shows how Rome's political crisis was fundamentally personal.

It began with the subversion of the individual to the state.

“Achievement was worthy of praise and honor, but excessive achievement was pernicious and a threat to the state. However great a citizen might become, however great he might wish to become, the truest greatness of all still belonged to the Roman Republic itself”

This did not sit well with everyone. Nor did the constant claustrophobia of big-brother-is-watching-you:

“The state had the right to know everything, for the Romans believed that even personal tastes and appetites should be subject to surveillance and review. It was knowledge, intrusive knowledge, that provided the Republic with its surest foundations.”

Showing how individual ambitions and family feuds born out of this repression snowballed into constitutional crisis, Holland argues:

"The Republic was not murdered - it committed suicide."

The book opens with Sulla, the ruthless dictator who marched on Rome and slaughtered his enemies in a bloodbath of “proscriptions” – a euphemism for legally sanctioned murder.

His lesson? If you have an army, you can rewrite the rules. Julius Caesar wasn’t the first to figure that out—he was just the one who did it best.

The core of Rubicon is the power struggle between three titanic figures: Julius Caesar, Pompey the Great, and Marcus Licinius Crassus.

This trio, known as the First Triumvirate, was less of a political alliance and more of a time bomb.

Realising that the only way to whet their ambition was to look beyond Rome, they set out invading neighbouring lands under the guise of protecting Rome from future aggressions.

“It was an article of faith to the Romans that they were the most morally upright people in the world. How else was the size of their empire to be explained? Yet they also knew that the Republic's greatness carried its own risks. To abuse it would be to court divine anger. Hence the Roman's concern to refute all charges of bullying, and to insist they had won their empire purely in self-defense.”

Crassus, Rome’s richest man, gets himself killed trying to fight the Parthians.

Pompey, Rome’s greatest general, returns to a hero's welcome in Rome, and declares his ally, Caesar, a threat to the Republic.

And Caesar, ever the gambler, takes the ultimate risk—marching his army into Italy and daring the Republic to stop him.

Well, you know how that story ends.

What Holland gets right

His character portraits are alive. Holland writes these men as deeply human, full of ambition, paranoia, and fatal miscalculations.

Pompey, for all his victories, misreads Caesar at every turn.

Caesar emerges as both brilliant and pathologically self-absorbed:

"To be Caesar's friend was to be his subordinate."

And Crassus was:

"...a man who measured everything, even himself, in terms of profit and loss."

Meanwhile, Cicero is brilliant but fatally indecisive. Following him, the Senate dithers, desperately clinging to tradition while Rome tears itself apart.

“Here, then, was one final paradox. A system that encouraged a gnawing hunger for prestige in its citizens, that seethed with their vaunting rivalries, that generated a dynamism so aggressive that it had overwhelmed all who came against it, also bred paralysis.”

And then there is Holland's style.

He writes like a novelist, turning political debates into life-or-death showdowns and making you feel the tension in every betrayal and battle.

When Caesar finally makes his fateful decision to cross the Rubicon, you feel the weight of history tipping.

The book is filled with sharp, cinematic moments: the chaos of Cicero’s speeches, the brutal purges of Sulla, the eerie silence of Caesar’s assassination.

You know how the story ends, and yet, you’ll be on the edge of your seat anyway.

What might disappoint you

If you’re looking for deep political analysis, you won’t find it here. Holland is a storyteller first, a historian second.

He sometimes prioritises drama over nuance, painting Rome’s decline in broad, sweeping strokes rather than diving into the finer details.

The book is also very Caesar-centric, as the name suggests. While he covers figures like Cicero, Cato, and Brutus, they often feel like side characters in Caesar’s grand drama.

For a more balanced view of the Republic’s fall, you might need to look elsewhere.

The Verdict: A Must-Read for Rome Lovers

Rubicon succeeds brilliantly at making the Republic's fall feel both inevitable and tragic.

Holland shows how a political system designed for a city-state collapsed under the weight of empire, and how personal ambition combined with institutional decay to destroy a 500-year-old democracy.

The book's genius lies in making ancient events feel urgently relevant without straining for modern parallels.

You'll finish it understanding not just how the Republic fell, but why such falls keep happening throughout history.

"The Romans were the first to suffer the consequences of their own success."

They wouldn't be the last.

As Holland shows, sometimes crossing the Rubicon doesn't require an army - just a political class that puts personal ambition above institutional stability.

Read Next:

If you want a broader look at Rome’s entire history, Mary Beard’s SPQR is an essential read.

For fiction, Robert Graves’s I, Claudius gives you all the scandal and betrayal Holland skips.

And if you want more of Holland’s cinematic storytelling, his Dynasty covers the rise of the emperors who came after Caesar—because, as it turns out, Rome’s chaos was only just beginning.