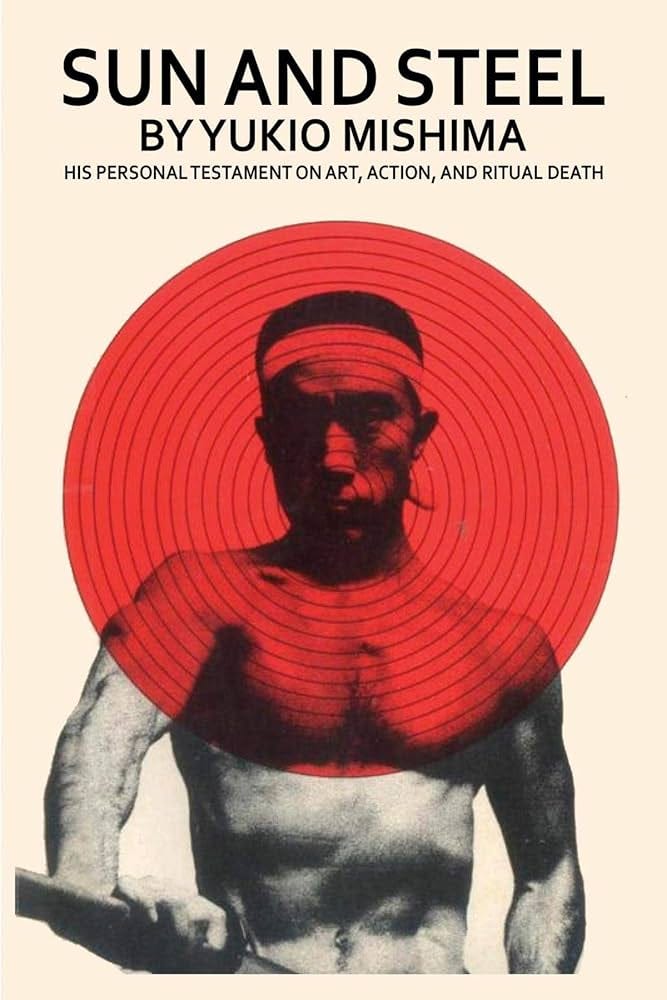

In 1970, Yukio Mishima — Japanese literary phenomenon thrice nominated for the Nobel Prize — led a failed coup attempt at Japan’s Ichigaya military base. With four members of his private militia, the Tatenokai ("Shield Society"), he seized a general and demanded Japan’s Self-Defense Forces rise to restore imperial rule. Addressing the assembled soldiers from a balcony, Mishima delivered a fiery speech about patriotism, spiritual decay, and the emperor’s sanctity — only to be met with jeers. Realising his vision would not materialise, Mishima returned inside and performed seppuku, ritual samurai suicide. The act was theatrical, political, and deeply personal — a final performance.

What kind of thinking drove this brilliant man who lived by the pen to die by the sword? Mishima's own Sun and Steel (1968), published two years before his coup attempt, is probably the closest you can get to the answer.

The book is Mishima’s metaphysical diary of his transformation from frail literary genius into chiseled warrior-poet.

"From the start, I wanted a body. I wanted to be transformed into a man who had both a literary mind and a muscular body. I wanted to be a writer who could also act, fight, and die."

But it's not a memoir in any conventional sense. Mishima isn’t telling you about his childhood or his literary ascent. He’s telling you what it feels like to abandon the mind in favour of the body, to unwrite yourself through sweat and iron. At just over 100 pages, the slim volume is a deeply personal, often feverish treatise. Some of it is moving. Much of it is disturbing. All of it is provocative.

Sun and Steel has never been widely celebrated, but it's never been forgotten either. No other writer has merged gym culture and metaphysics this unapologetically. The book's cult status has only grown, especially appealing to anyone who’s ever stared into a mirror and seen either a Greek statue or a lost cause, wanting to make something divine out of either. Artists who loathe their own bodies, bodybuilders who wish they could think in metaphor, readers who don’t mind a bit of fascist undertone — Sun and Steel has been their weird little gospel.

The intellectual who hated intellectualism

Sun and Steel presents itself as a meditation on the body, the physical self, and what Mishima saw as the failures of modern intellectualism. He grew disillusioned with writing, believing that language abstracted experience beyond recognition, plunging us into a dark night to fumble around in.

"Words are a medium that reduces reality to abstraction and to which, moreover, only a certain portion of reality is accessible. In the realm of the spirit, they possess truth, but not reality. They are real only in the realm of reason."

[...]

"Language had already begun to pall. What I was seeking was not the kind of truth that could be explained in words, but, on the contrary, a truth that could not be expressed in words — the truth of the body."

The only solution is to step into the "sun" which represents pure, elemental truth: heat, pain, clarity, the undeniable presence of the body under the indifferent force of nature. The sun burns away all illusions, especially the literary and cerebral indulgences he came to resent. The sun reveals the body's own capacity to think, to know, and to communicate.

"The flesh carries a certain philosophy of its own, and it is the role of the flesh to demonstrate that philosophy — silently, uncompromisingly, and with deadly clarity."

To cultivate this body to its perfect form, one must rigorously train with "steel" – discipline, strength, weaponry. It’s not just about muscle, but about a form of truth that words can’t reach: the truth of pain, of limits, of mortality.

“The groups of muscles that have become virtually unnecessary in modern life, though still a vital element of a man’s body, are obviously pointless from a practical point of view, and bulging muscles are as unnecessary as a classical education is to the majority of practical men. Muscles have gradually become something akin to classical Greek. To revive the dead language, the discipline of the steel was required; to change the silence of death into the eloquence of life, the aid of steel was essential.”

Together, sun and steel become a harsh creed: salvation not through thought, but through sweat, blood, and confrontation with death. Mishima’s turn to bodybuilding and martial aesthetics was a desperate attempt to reclaim meaning from a modern world he saw as flabby and spiritually empty. He believed the body was the only honest thing left, and to forge it like steel under the sun’s merciless light was to make one’s life — and death — real. It’s both a critique of modernity and a tragic manifesto for those who believe beauty must end in violence.

"A man whose flesh is trained to perfection cannot help but be aware of death. Death exists as a final destination, a limit, and this awareness gives shape to the body."

Though he was writing from post-war Japan, Mishima is steeped in European thought. Nietzsche looms large, with his emphasis on will and transcendance. There's Heidegger’s disgust with inauthentic existence, with echoes of Thomas Mann's Death in Venice in its aestheticisation of the body, and Jean Genet's transgressive physicality. But even more central is the traditional Japanese samurai ethos — bushidō — which prized physical discipline, loyalty, and an almost mystical approach to death.

Beware, though. He distorts as much as he draws. He cherry-picks from these traditions to serve a larger, deeply personal mythology. This is a man who turned his own life into a kind of gesamtkunstwerk — total art — a performance piece in prose, flesh, and eventually, death. _Sun and Steel_ is less a book and more a torso: beautiful, cold, and sculpted into terrifying perfection.

Where Mishima shines

Reading Sun and Steel feels like doing sit-ups while a philosopher shouts koans at you. It’s urgent. It’s disjointed. It’s frustratingly elegant. And then it suddenly breaks your nose with a sentence like:

“To cut away one’s flesh with words is as distasteful as to cut away one’s words with flesh.”

You’ll read that twice, wonder if it’s genius or nonsense, and then reread it again. That’s the rhythm of this book: confusion and awe doing tango in your head.

There’s no denying the power of Mishima’s prose. Even in Hiroaki Sato’s fluid, faithful translation, it hums with a tight, cold fire. At times, the prose will intoxicate you. Then, suddenly, it will turn cold, militant, extreme. That dissonance is essential. Mishima doesn’t let you settle. He doesn’t want you to agree. He wants you to wake up.

There’s a romantic violence in his metaphors. He treats discipline not as a means to success, but as a sacrament. That conviction, no matter how deranged, makes the writing pulse with raw beauty.

More importantly, he offers a model of sincerity that we don’t often see anymore. In an age of ironic distance and performative speech, Mishima means every word. You might not agree with him, but you won’t doubt that he believes what he says — enough to put his own body on the line.

What might disappoint you

Often, the book is insufferable. Mishima’s obsession with his body, his contempt for intellect, his longing for death — it curdles into something grotesque. He talks about purity like a demagogue. He fetishises pain. He romanticises militarism and drips condescension on anyone who doesn’t see the world in steel-edged absolutes.

“If the concept of the hero is a physical one, then, just as Alexander the Great acquired heroic stature by modeling himself on Achilles, the conditions necessary for becoming a hero must be both a ban on originality and a true faithfulness to a classical model; unlike the words of a genius, the words of a hero must be selected as the most impressive and noble from among ready-made concepts.”

There’s also the whiff of fascism, and not in a subtle way. His aesthetic is authoritarian, his tone dictatorial. The book tiptoes toward ideology but never clarifies it — a dangerous ambiguity wrapped in poetic rhetoric. It’s seductive, and that’s precisely the problem.

“Even though the world might change into the kind I hoped for, it lost its rich charm at the very instant of change. The thing that lay at the far end of my dreams was extreme danger and destruction; never once had I envisaged happiness. The most appropriate type of daily life for me was a day-by-day world destruction; peace was the most difficult and abnormal state to live in.”

Mishima isn’t trying to be right: he’s trying to be incandescent. You don’t read Sun and Steel for a moral compass. You read it because it dares to be insane with purpose. It’s a singular document, a testament to the madness that occurs when a brilliant man tries to muscle his way into the eternal.

The Verdict: Sinewy Descent into Madness and Metaphor

Sun and Steel is not your typical weekend read. It is not comforting, it is not linear, and it certainly doesn’t play nicely with the values we like to project. But it is important, if for no other reason than the confrontation it provokes between thought and action, body and spirit, literature and life.

For instance, if Yukio Mishima were alive today, he’d take one look at your Instagram filters, TikTok dances, and profile bios bloated with emojis and scream into the sun. His whole project in Sun and Steel is a furious rejection of abstraction, and what are our digital lives if not a cathedral built on abstraction? Words without weight, faces without bodies, identities without pain. Mishima wanted to return to the sweat, blood, and bone of reality. You want a six-second story highlight. He would’ve seen our pixelated performances as the final betrayal: the mind devouring the flesh completely.

Sun and Steel is a strange, dangerous little gem: the kind of book that doesn't ask to be liked, only endured. It's narcissistic, infuriating, beautiful. Reading it won't make you a better person. But it might make you see yourself, body and mind, in harsher, sharper light. You might start noticing how your own embodied experience influences your reading of the text. Your moments of discomfort or resistance will signal important ethical or philosophical boundaries being tested. Whether that’s a blessing or a curse is entirely up to you.

Read Next:

If you’re still standing after Sun and Steel, and you're itching for more beautifully written existential firestorms from Mishima, go for Confessions of a Mask, the semi-autobiographical novel that made him a literary star at the age of 24, or his The Temple of the Golden Pavilion, which drips with nihilistic poetry.

For more recent fiction, go for Chuck Palahniuk's Fight Club — a spiritual cousin in its glorified bruises and disdain for soft masculinity. You might also appreciate Haruki Murakami's The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, which explores similar themes of physical experience versus intellectual understanding but with more gentleness.

On the non-fiction side, pick up Albert Camus’s The Myth of Sisyphus to see what rebellion looks like without a sword. Or try Ernest Becker's The Denial of Death, which might be the sanest book ever written on why people like Mishima do what they do.